Soon after I became a Christian, almost 30 years ago, I found an author/speaker that I liked very much—a no-nonsense, straight-talking woman who would help shape many aspects of my early Christian walk. I owe a tremendous debt to Elisabeth Elliot, her books, and her radio program, Gateway to Joy, and I’m grateful to God for placing her in my life at just the right time. Her influence has made me a better person, and a better Christian.

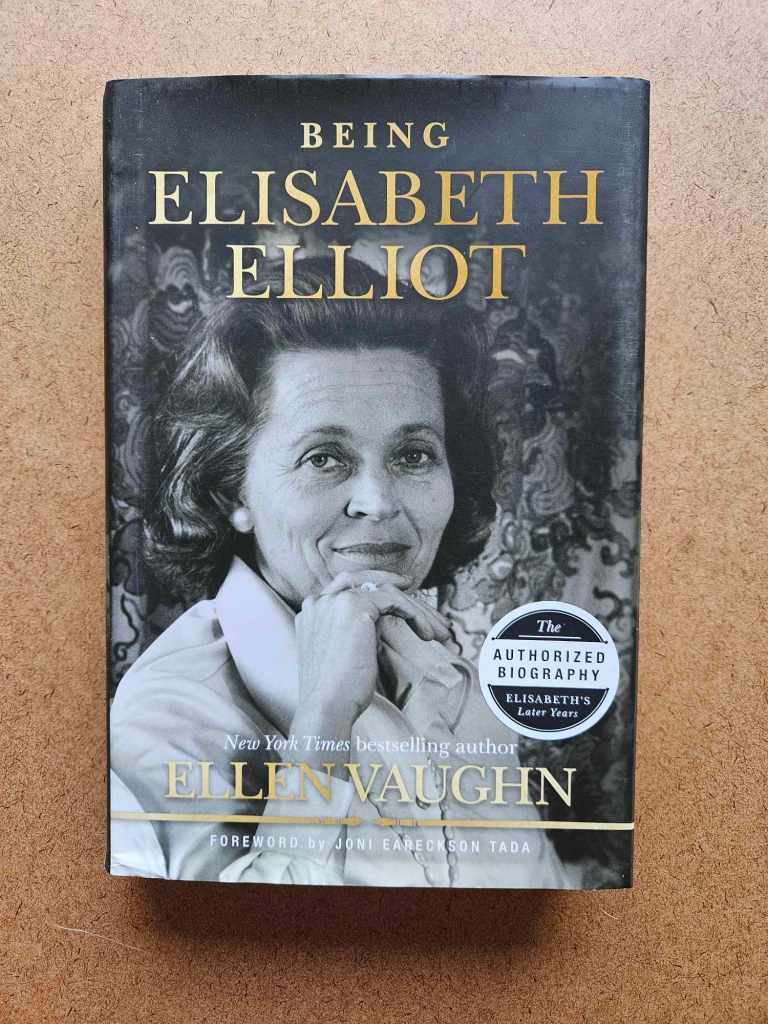

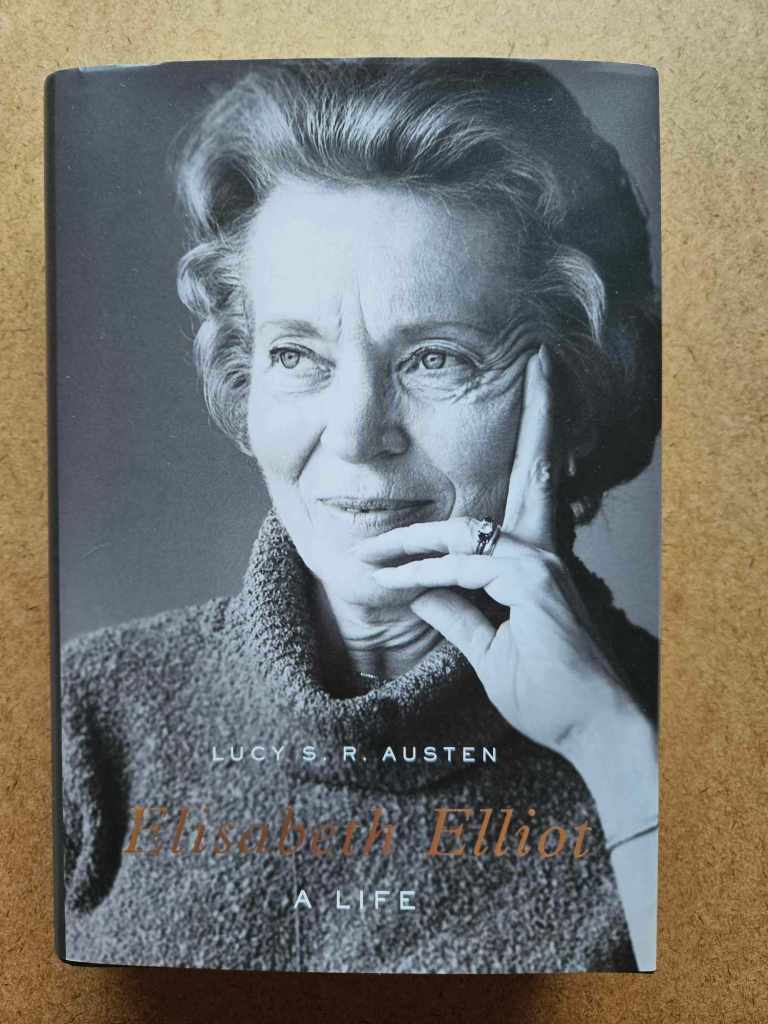

So I was thrilled to see, a few years ago, that new biographies about her were in the works. First came Ellen Vaughn’s Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, part one of a two-volume set published in the fall of 2020 by B&H Books. Then came Lucy S. R. Austen’s Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, published in June 2023 by Crossway. This was followed very quickly by Vaughn’s highly anticipated second volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot, published in the fall of 2023. (I think these dates are important, as you’ll see.)

The two biographies (counting Vaughn’s two volumes as one bio) have similar titles, similar covers, and were published right around the same time. Vaughn’s is officially the authorized biography, but in my mind, Austen’s is the definitive one; of the two, it’s the most complete, must-read biography of Elliot’s entire life.

I read the Vaughn biographies first, and the first volume of the two, Becoming Elisabeth Elliot, is good. It goes into great detail about Elliot’s early life, including her time as a missionary among the Waodani tribe in Ecuador, both before and after the death of her first husband, Jim Elliot. But even though I liked this book overall, while reading it I got the feeling here and there, in subtle ways, that Vaughn wanted to make sure her readers know that she doesn’t agree with Elliot’s views on certain topics, particularly topics related to men and women or the roles of husbands and wives in marriage. When she refers to these topics in Elliot’s writings, Vaughn doesn’t quote from or summarize Elliot’s views; instead she assumes that readers already know, or tells them to go read Elliot’s work for themselves. Vaughn seems to believe that contemporary readers would naturally agree with her that Elliot’s ideas are outdated or incorrect. Vaughn also inserts herself into the book in multiple places (her thoughts, how writing the biography affected her, etc.), and I’ll be honest: this was a huge turnoff for me.

Still, Vaughn is a good writer and I liked the book enough to buy volume two. But that second volume had a later publication than perhaps anyone had anticipated. I’m sure the publisher would have liked to get it into readers’ hands long before Lucy S. R. Austen’s one-volume bio was publishing with Crossway, and the fact that those books published so close together (this is speculation on my part) might have contributed to the problems with Vaughn’s second volume, Being Elisabeth Elliot.

Two indicators that this second volume may have been rushed to publication are the typos throughout (misspelled names, etc.), and the fact that there are no photos in Being Elisabeth Elliot. There were many photos in the first volume, just as you’d expect in a biography of an important person from recent history, but the second volume has none.

Throughout Being Elisabeth Elliot, Vaughn continues to subtly or not-so-subtly insert her own thoughts, opinions, and life experiences. Sadly, Vaughn’s husband was seriously ill and died during the writing of the book; no doubt this contributed to the delay in publication. Now, I’m not cold-hearted; I feel sad for Vaughn that she must have continued writing throughout this terrible time in her life. However, I didn’t want to read about Ellen Vaughn in Being Elisabeth Elliot. I wish she had told this unfortunate connection to her own story (if at all) in an Author’s Note, instead. I can’t help but wonder if no one at B&H Books wanted to step in, due to the author’s grief, and set this book on a different track. Or perhaps the personal, confiding tone from the author was what they wanted for Elliot’s authorized biography (I can’t imagine thinking that would be a good thing, but I’m trying to give the benefit of the doubt).

It’s possible that Vaughn’s grief and understandably very difficult personal life changes could also be the reason for the biggest problem with Being Elisabeth Elliot: this biography devotes just ten pages to the last 38 years of Elliot’s life. The reason given is that Elliot’s journals covering those years were destroyed by her third husband. Was there was an agreement with the family to essentially end the biography with that third wedding? I don’t know why else the last 38 years of Elliot’s life would be breezed over as if nothing of note happened during this time in her personal or professional life. That’s when many modern readers actually discovered Elliot and were heavily influenced by her, myself included. So the omission is disappointing.

The Vaughn biography was authorized by Elliot’s family, which means that Vaughn had access to Elliot’s journals, whereas Austen did not. But there’s a negative side to that unfettered access to the personal journals: Vaughn’s reliance upon this resource, along with her storytelling writing style, takes the second volume into the “too much information” territory. For instance, you’ll find very little information on Elliot’s later speaking or writing career in Being Elisabeth Elliot, but you will find more than you probably wanted to know about Elliot’s sex life with her second husband, followed by excruciatingly long (28 pages), detailed descriptions of his agonizing illness and death. I can’t imagine that Elliot ever intended for any of these quotes from her journals to become public knowledge. I found myself cringing while reading these intensely personal aspects of her life, embarrassed for the exposure of such details.

After I finished reading Being Elisabeth Elliot, I didn’t have the emotional energy right away to tackle Lucy S. R. Austen’s one-volume, 500+-page biography, Elisabeth Elliot: A Life, even though I thought I would probably like it. I had to put some distance between these books. I later found Austen’s bio exactly as I hoped it would be. Unlike Vaughn’s narrative, which uses a more imaginative storytelling style, Austen’s book is more objective and more scholarly (but still enjoyably readable)—a much more traditional biography. She apparently didn’t have access to Elliot’s personal journals, but that doesn’t detract in the slightest from her well-researched book.

Austen’s coverage of sensitive topics is thoughtful and, well, sensitive. For example, she explains the aggressive radiation and chemotherapy treatment regimen that caused Elliot’s husband such agony in the context of the medical establishment’s approach to cancer at the time, and the lack of hospice availability in the U.S. We learn about how terribly hard this disease was on Elliot and her husband, and how they attempted to cope with it, but we’re spared the highly personal, graphic, day-to-day details and quotes.

Austen’s book is where you’ll find details on the entirety of Elliot’s life, including 47 pages (admittedly, still short) on the last 38 years: her tremendous popularity both in print and on the radio; the publication of each of her books; her writing and speaking schedule, her family, her grandchildren, her struggles with time and energy, and her daily patterns of study and devotions; her Alzheimer’s diagnosis and what followed; and, sadly, her third marriage to an extremely controlling and unpredictably angry man. Throughout the book, Austen gives a thorough and objective portrayal of Elliot based on her extensive research and findings of a decade of study.

Both biographies show Elliot to be a flawed human being. This may be hard for some readers to accept, and if you suspect you might be one of them, I’d advise not reading either biography. But for those who were influenced by Elliot and want to know more about this formidably intelligent and well-spoken woman, including all that made her imperfectly human just like you and me, I highly recommend Austen’s definitive Elisabeth Elliot: A Life. If you’d like to read about her life more like a story, with short, breezy chapters packed with words from her journals as well as personal commentary from her authorized biographer (and if you’re ok with not learning much of anything about her life from 1977 to 2015), then pick up the two-volume Vaughn biography: Becoming Elisabeth Elliot and Being Elisabeth Elliot.

If I had to choose only one, I’d read Austen’s book, but overall, I’m glad I read both of these biographies of one of my heroes in the faith.

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases, which I use to offset the costs of running this site